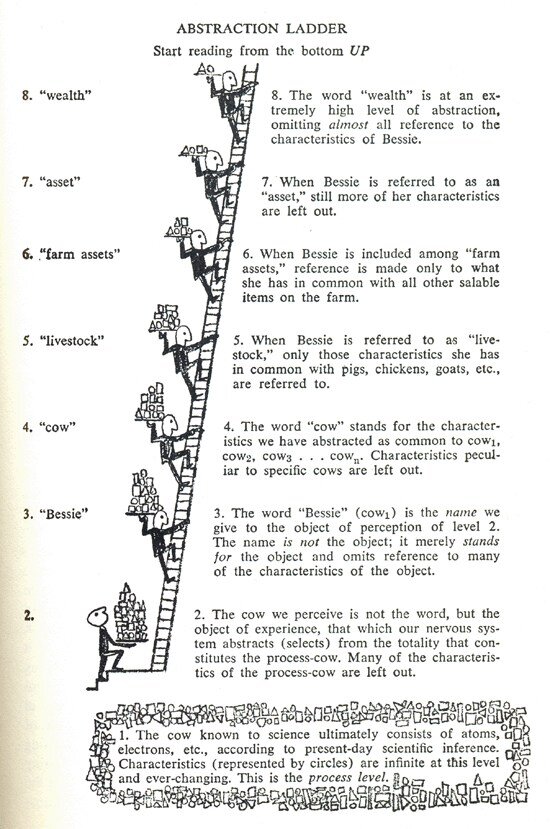

Language is thought in action. What does that mean, Tom? I'm glad you asked.

I don't want to crawl too far down a rabbit hole, but almost all of us subvocalise our thoughts. Subvocalisation is that inner monologue we hear when we read or think - you're likely subvocalising right now, reading this sentence. Yes, it's all very meta.

One of the ways we confuse ourselves is to skip the thought bit and think language is action. It isn't. It's just a thought, an idea. Communism the idea didn't kill 100 million people directly, those acting in its name did. (That said, it's still a bad idea.)

When we humans confuse thought with action, we do silly things like compose text messages in our head and forget to actually send them or have arguments against our colleagues in the shower (which we inevitably win.)

The problem with this is our nervous system often doesn't know the difference between what's perceived and what's real. We can think our way into anxiety and depression, aided by complex and repetitive trauma that's located in our viscera - our gut feelings, as it turns out, play a big role in our moods and emotional wellbeing.

This poses a problem for the "talking cure." According to trauma researcher Bessel van der Kolk, responding to trauma through medication and talking alone doesn't always work in isolation. I've been on mild anti-depressants/anxiety medication since high school. I can definitely attest to Dr. van der Kolk's assessment. In everyday situations, especially when we're feeling low, it can be attributed to the narrative we spin about ourselves.

Your brain will believe what you tell it is true. The root of depression, as put in a meme, is the result of nasty rumours you tell about yourself. So how can you flip the script, or at least try to?

What I Do

The first act is to open up and own what you say. If something doesn't feel right, ask someone you trust and talk it out. No, they might not understand. But at least you will get it off your chest. Join a support group, see a counsellor, do whatever suits you best. Always use the "I" statement. Not "you know" or "you know when..." No, I don't know. Own what you say and often the solution will become clear.

Second, journal. Keep a daily (or near enough) journal. Opening up by writing things down is not only good for tracking your own progress but getting clarity on your thoughts.

Truth isn't a convenience, it's a winner's mindset.

Third, tell the truth. Tell it to yourself, tell it to your loved ones, tell it to everyone around you, as hard as it seems. If you say "Oh, I tell the truth 90% of the time..." Well, how do I know I'm getting the 90% or the 10% that's BS? Truth is the currency of business. Hiding things, being dishonest, pretending everything's alright...reality always kicks down the door of fantasy. Always. Truth isn't a convenience, it's a winner's mindset.

All three elements are explained much better in the following books, which I recommend every businessperson read:

A Rational Guide To Living by Drs. Albert Ellis & Robert Harper, Ph.D

The Situation Is Hopeless, But Not Serious by Dr. Paul Wazlawick, Ph.D.

The Obstacle is The Way by Ryan Holiday

Daring Greatly by Dr. Brene Brown, PhD.

It doesn't always work, but it works much better than the alternative.