According to the great media ecologist Neil Postman, “the dictionary definition is not the end of an argument on its meaning, it is the beginning of one.”

Alfred Korzybski, a Polish engineer, thought so too. Coming out of the horror of the First World War, he asked: We as humans have progressed past Euclidian geometry and Newtonian physics, why do we still adhere to a language system dominated by Aristotle?

In short, Aristotelian language systems are built on the law of the excluded middle. A is A and cannot be B. Something is, in its totality. Grass is green. But look at it from the reverse perspective: Is Green grass in all cases? Something is amiss here.

Non-Aristotelian language systems are “fuzzier” - they do not deal in absolutes. Instead, they look at probabilities, offering different meanings resting upon how we deal with abstractions.

Language is thought in action. The sounds we make, the letters we write, the way we move our hands and faces is our way of making our inner thoughts come alive in the real world. We then interpret those signals and process them as thoughts of our own.

In this process, some of the “true” meaning is lost. The signal is interrupted by noise. Sometimes that noise is of our own making.

In the 19th Century we hit the limits of Euclidian geometry; in the early 20th we hit the limits of Newtonian physics. In the 21st, we are seeing us hit the limits of Aristotelian language.

Non-Aristotelian language systems ask this question: what is going on? The language must shape the observations and be conscious that our words do not cover every single aspect of whatever is described.

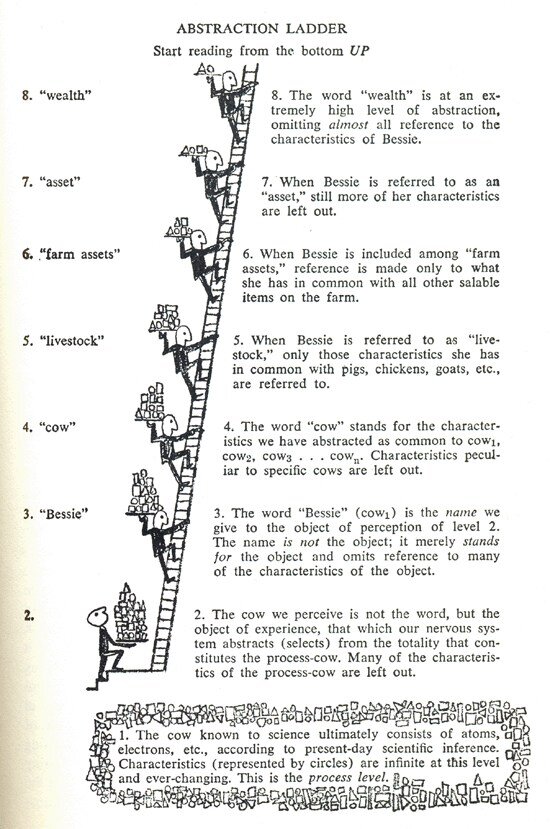

S. I. Hayakawa’s Abstraction Ladder.

Look at Hayakawa’s Ladder. Samuel I. Hayakawa was a US Senator and General Semanticist that borrowed from Korzybski’s ideas. We as humans confuse logical levels all the time. The abstract concept of “wealth” could mean almost anything lower on the ladder. “Bessie” the cow, one particular cow among many, is lost amongst that “wealth.”

One could argue the art of political communication is pitching high abstract concepts at as many people as possible and moving up and down the ladder depending on the political objective.

Not only that, but words can have different meanings depending on context. The phenomenon of “fake news” is often a deliberate confusion between more abstract terms and concrete terms. Concrete being what we see or hear directly; abstract in the sense of what we can infer; and “defined” by what we judge to be true. For example:

Observation: My neighbour Joe hasn’t returned the hammer he borrowed from me a month ago.

Inference: Joe is lazy and careless about other people’s belongings.

Judgement: Joe is a bad and untrustworthy person.

Now let’s observe this further and get more information.

Observation: My neighbour Joe hasn’t returned the hammer he borrowed from me a month ago.

Inference (based on further observation): Joe is a widower. He’s under lockdown with three kids and has been laid off, he must have his hands full at the moment.

Judgement: Joe is likely depressed and anxious. I won’t bother him with such trivial things at the moment.

I write this because I’m tutoring a friend of mine in writing university essays. I explained this concept to him, and he threw his hands up in the air. “Was I away when they taught this in school?”

I told him they don’t teach this in school.

He was shocked.

I thought about it for a tick. I was shocked too.

What if next to no one is taught this at any level? Why are we running around using inventions based on current science and using a language built for primitives?

Is this not a recipe for disaster?

Or are we living in the oven already?

Let’s hope not.